Today I want to talk about stylization versus gesture. A very common misnomer online is to call a simplified, or stylized drawing, a “gesture drawing”. And this has directly led to the misconception that Nicolaides’ gesture drawing is either “just messy drawing” and/or it is “too difficult for beginners”.

Let’s break it down.

Learning to understand the complexity of the figure through simplified, or basic shapes is a method that many beginners find extremely useful, and it yields quick and satisfying results because it is so outcome oriented. We all need wins in our learning curve. This method is like learning the letters of the alphabet.

Equally foundational is mark making. This is like learning how to pronounce, or express, the letters. Mark making = expression. The way you make a mark is expressive, because drawing is a language!

Expression therefore is just as important to understand when it comes to figure drawing, as is drawing something complex in an easy way. The way you express yourself through line is one of the most fundamental, foundational and vital things to learn about drawing, and about your way of drawing. Whether you draw a simple, clean line or an expressive, dynamic mark, that is for you alone to discover.

But expressive mark making that might look “messy” is no less considered just because it looks that way. In fact it’s a response or reaction to a subject that is artistic in nature, for reasons that I will explain here.

To make a simplified or stylized drawing of the human body, the steps involved dictate the following: simplify the forms with cylinders and ovals; turn a complex contour into a simple c-curve; use clean, smooth lines… There is no spontaneity or response. The resulting drawing is necessarily stylized because it is made up of simple, universally recognizable shapes (cylinders instead of bumpy forms, smooth c-curves instead of nuanced contours). And moreover, this can easily be replicated by anyone else who follows the same steps, and thus generic, hyper stylized drawings tend to look indistinguishable from one another in terms of unique artistic expression.

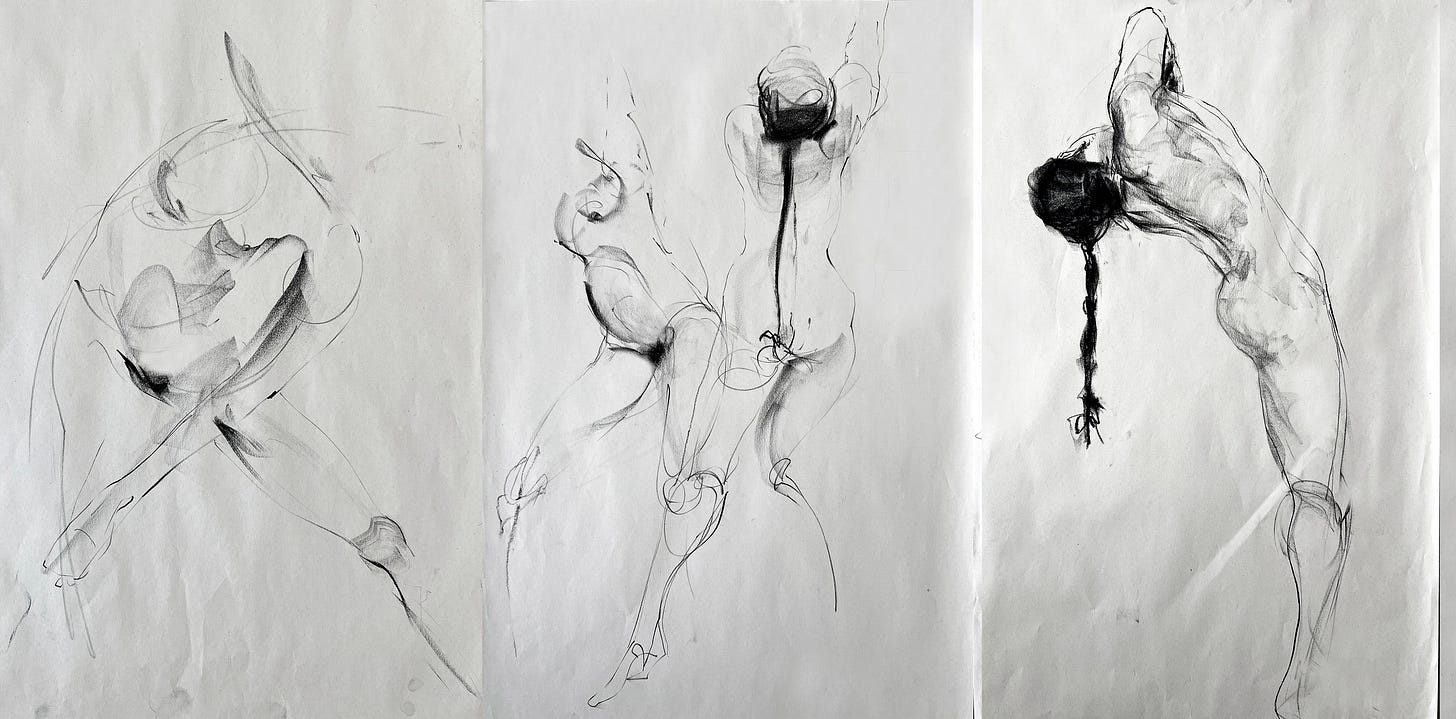

To make a gesture drawing, the steps required are: follow what you see as movement through the form; try to put on to the page your idea of the pose as a whole, or your idea of what the feeling is in the pose; and be spontaneous: get the marks down quickly, before you have time to alter, change or make judgments about them. What you end up with might be a bunch of lines and marks that don’t necessarily match the anatomical points of the body, and because you draw directly and fast, it might look like you are drawing “messy” or in a meaningless way. But the result is a drawing that is not universal, neither is it meaningless. It has a meaning because the lines and marks are direct expressions of how you interpret the pose.

Thus, in a quick gesture drawing, the “meaning” you’ve made is actually profound.

And because both the way you observed the model, and the marks you chose, are unique to you, the meaning is such that that no one else could ever make the same drawing, even if they follow the exact same steps that you did.

The outcome of a gesture drawing is not replicable in the way a stylized drawing is. For this simple reason: what you see as the movement, the idea or the feeling of the pose is not the same as what someone else will see. And certainly the way you draw it will never be the same as the way someone else will draw.

In effect, a gesture drawing teaches you how to make artistic choices that are individual to you.

Next time you are in life drawing, look at how many different drawings of the same pose there are. Not one of them is the same drawing, not one of them is in the same “style” - each one is an expression of the artist who drew it. Expression is individual.

Consider these works below:

A Jackson Pollock painting is certainly abstract. It’s definitely conceptual, and in its execution it’s nothing if not gestural and expressive. Is it meaningless, or mindless?

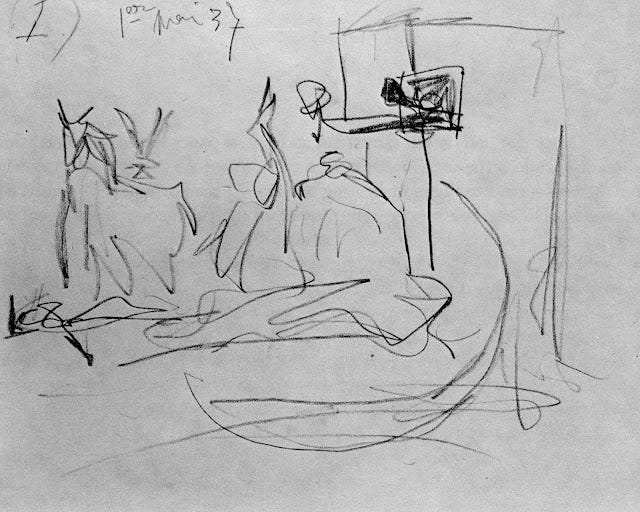

Picasso’s drawing for Guernica might look like simply a “messy sketch,” but it is an expression, direct from his mind, of his vision for possibly one of the greatest artistic achievements of modern art.

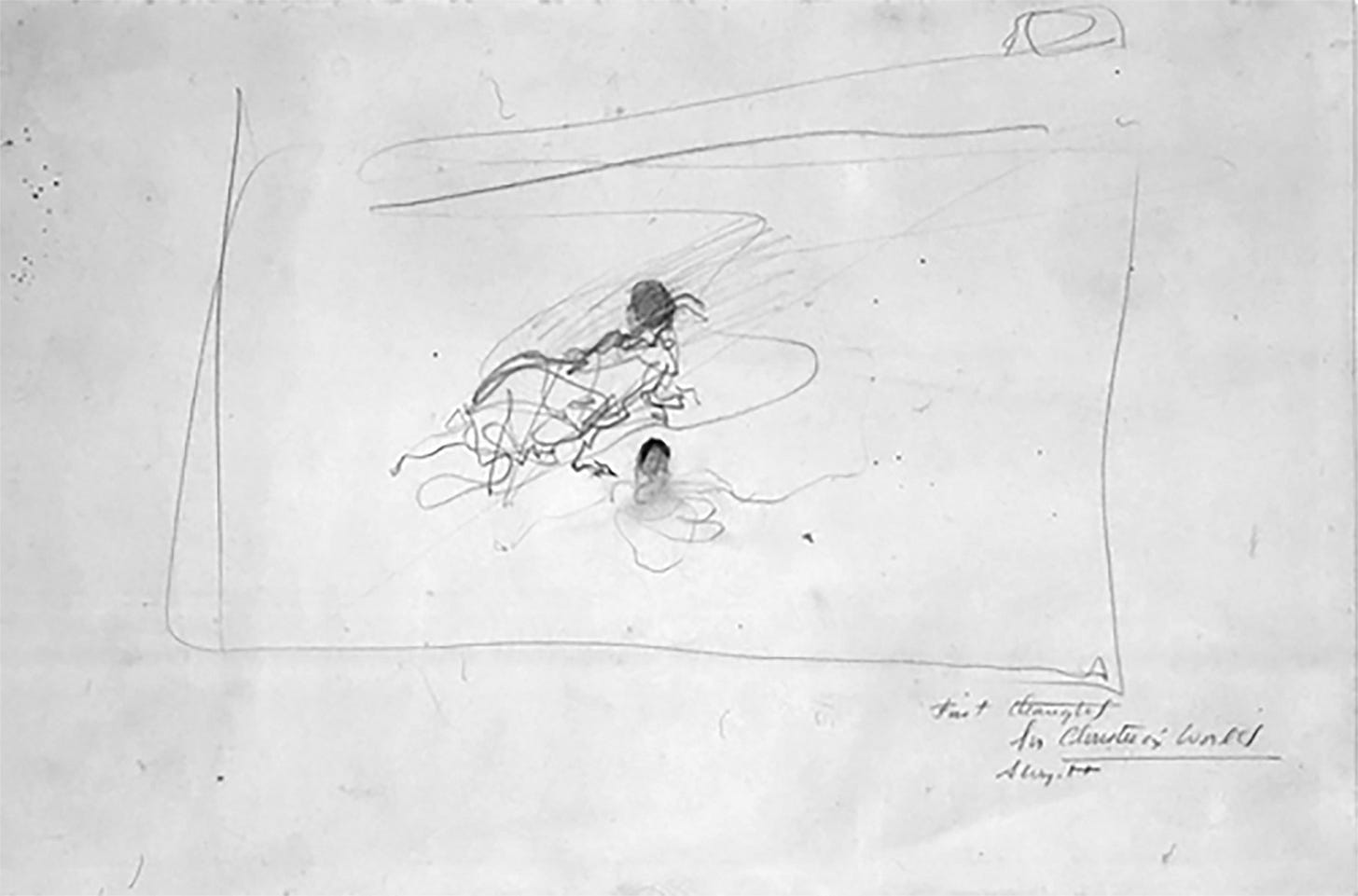

Is Andrew Wyeth’s “First Thought for Christina’s World” mindless? Or, is it a thought form made visible on a piece of paper that expresses the dramatic and poignant beauty that was to come through in his final painting.

All of these works are gestures. All are spontaneous and expressive. Far from dismissing them as messy or incoherent, they are direct visualizations of what was in the mind of the artist.

The choices that an artist makes in a simplified or stylized drawing of the figure might be more calculated and careful, but the choices made in a gesture drawing are no less valid, or artistic, for being un-mediated, direct and responsive.

The reason so many artists want to learn gesture drawing is because gesture as a method of drawing, is a direct expression of an artist’s visual language, made explicit on paper, with marks that can only come from their own hand.

And the reason so many can’t do gesture drawing is because they are ignoring the feeling and trying to draw simplified shapes instead: when you try to draw the gesture by focusing on the figure, you get a drawing of the figure and not the gesture.

“The general public often doesn’t respond well to gesture drawings because they may have trouble “reading” them, and since they are done rapidly, they may feel that drawings which take hours longer have to be better. It is this very quality of spontaneity which artists and connoisseurs respond to, since they know how difficult it is to achieve”

Robert Kaupelis, “Experimental Drawing”, p 27

The next portion of the post is for paid members of this newsletter. If you would like to continue reading and learn about our upcoming Book Club, consider joining for $6 a month. It helps me out immensely and gives us the opportunity to work together through weekly drawing challenges.